The Potential of Corporate Architecture in Corporate Communications

How architecture can make a vital contribution to the effectiveness of corporate communication

Prof. Dr. Dieter Herbst

University of the Arts Berlin, Germany and University of St.Gallen, Switzerland

Bettina Maisch

University of St.Gallen, Switzerland

Conclusion and Outlook

The examples cited show that German car manufacturers in particular have recognised the importance of corporate architecture and by way of various applications have translat-

ed their brand values into three-dimensional structures – so-called “carchitecture”. It can be assumed that the importance of architecture in corporate brand communication since, on the one hand, global competition is increasing and, on the other hand, it is becoming increas- ingly difficult to reach target groups through communication. Corporate architecture pro- vides an opportunity to use new methods of profiling in competition. One challenge is to translate the brand values into a three-dimen- sional architecture, transforming the brand into something that can be experienced with the senses. Another is that contractors and architects have to link enduring architecture with changing brand values: the buildings must convey continuity (which is essential for brands with regard to recognition and trust-building) while allowing room for change and further development – both in terms of the brand val- ues conveyed and the requisite use concepts. If more and more companies use architecture as a means of conveying their brand values, one final point to note is that companies have a responsibility to exercise societal responsi- bility with regard to the implementation. This means that the brand or company building must be integrated into the urban space such that cities are not allowed to degenerate into mere architectural advertising billboards.

Imagery research has for many years illustrated the great importance of vivid mental images for human behaviour. However, according to studies, to date only very few companies have been successful in creating clear mental images among internal and external reference groups. Corporate architecture provides an excellent opportunity for this, because corporate architecture, as a visual image, is processed and learned in a unique way by special areas of the brain. What is essential in order for corporate architecture to be effective as an indication of the company's personality is an underlying strategic concept for its use in corporate communication. This concept is the blueprint for a systematic long-term approach, leading internal and external reference groups to learn to quickly and unequivocally associate the building in question with the company. Furthermore, corporate architecture triggers strong positive feelings that lead these images to be learned even more quickly and processed on an even deeper level.

In this way, corporate architecture can contribute to the internal and external reference groups behaving more positively on the basis of these clear mental images of the company than they would without these mental images

The situation in companies

Over the last few years, companies have changed dramatically: they have become more complex, more international and faster (Hitt et al. 2002). The reasons for these develop- ments are the increasingly tough conditions on all markets; these conditions include growing competition between companies for custom- ers, the interchangeability of products and the decline in customer interest in communication (Aaker 2004, 2007).

These changes within companies have led to disorientation and loss of trust among the in- ternal and external target groups – they lack a clear image characterising the company and making it unique. This unique image is, how- ever, fundamental in order that the internal and external target groups can decide quickly and in a targeted manner whether or not to support a company through their specific be- haviour (Block 1983, Dowling 1986, Fombrun 1990, Fombrun 1996, Herbst 2009).

Only a handful of companies have been able to build and systematically develop such effective images. One reason for this is that they tend to rely on global image databanks, the result of which is that many companies show the same images. Another reason is that the images are interchangeable and reflect clichés within the various sectors – banks show the customer in talks with an advisor, while pharmaceuti- cal companies invariably show doctors, white coats and stethoscopes. Herbst’s (2005) quali- tative study of the top 15 DAX-listed compa-

nies shows that the respondents were not able to link unique images with companies or even to allocate them to a strategic corporate imag- ery that fulfils the criteria of a high level of ef- fectiveness. Only companies such as BMW and Mercedes were able to trigger clear mental images, but these are product associations, not mental images of companies.

The importance of corporate architecture for mental images of companies

Images are processed by different areas of the brain than language (Paivio, 1971, Paivio 1986, Pylychyn 1981, Finke 1989); they can be perceived quickly; they can be absorbed im- plicitly without effort; they can be processed quickly and easily and stored for a long period of time; they are stored – and thus learned – even more effectively the more emotionally appealing they are (“emotions are an engine for learning”)

Perceptive images result in mental images. According to studies, mental images have a particularly pronounced effect on behaviour (Kroeber-Riel 1996, Imagery 2006, Fichter/Jo- nas 2008). The advertising trade has known of this outstanding effect on behaviour for some time already: tests show that consumers prefer Pepsi cola in blind tests. If, however, they are able to see the trademark, they prefer Coca- Cola, which they link with mental images from advertising (Chernatony/McDonald 1992). Other studies show that the clearer the mental image of a company, the greater the readiness to purchase shares in that company (Imagery 2006). Furthermore, mental images are more significant for the evaluation of a company than general image profiles.

Corporate architecture has the potential to lead to the creation of clear, unique mental im- ages in the minds of the internal and external target groups. Today, there are already many examples of the way in which corporate archi- tecture can shape the imagery of a company, as the examples of Swarovski, Disney, Lufthansa, SONY and BMW illustrate. The contribution of corporate architecture could, for instance, be evaluated according to whether and to what extent customers are prepared to choose one company over another on the basis of mental images of the corporate architecture.

The two most important prerequisites for ef- fective corporate imagery are vividness and likeability (Block 1983, Cui/Jeter/Yang/Mon- tague/Eagleman 2007). To ensure that these are fulfilled, the corporate architecture ought to be based on a strategic concept. This con- cept determines, on the basis of the unique corporate identity, how the corporate archi- tecture can convey this identity and how to continually develop this.

An evaluation carried out by Herbst (2005a) of 478 images used in German news coverage during the period from 1 February to 28 Febru- ary 2005 illustrates the importance of corpo- rate architecture for a company’s public pro- file. The study showed that, after members of the company and the products, corporate ar- chitecture was the third most frequently used image. The photographs were, for the most part, neutral; the chance to present the com- pany in a positive light was not utilised. Com- pared with printed media, television makes far greater use of opportunities to show corporate architecture.

Case Studies:

Professional Corporate Architecture of the German Automobile Industry The automobile industry recognised the pow- erful communicative effect of public buildings at an early stage and uses architecture as an

additional design element in its brand ma- nagement and corporate communication. Some reasons for the great importance of cor- porate architecture in the automobile industry are increasing global competition and stringent regulation, which are forcing car manufactur- ers to use new communication methods to distinguish themselves from the competition. Another reason is that brand loyalty in this high-involvement sector is decreasing; through independent traders who sell models from various manufacturers, an important element of the relationship between the brand and the customer has been lost.

Recognition through architecture

Fierce global competition between car manu- facturers is transferred to automobile traders bound to the manufacturer: it is not uncom- mon to see several car salesrooms built side by side on main throughroads in urban centres. Here, architecture provides an effective tool for companies to clearly position themselves in competition and to help create recognition value among clients and potential customers. Visual differentiation of this kind through the uniform design of the car salesrooms can be seen in the case of German premium manu- facturer, Audi. As a brand, Audi stands for functional elegance, efficiency and technical innovations (Rosengarten & Stürmer 2005). Audi claims the top spot in terms of new de- velopments, as the claim “Vorsprung durch Technik” conveys through all communication measures. Audi’s brand values are translated into three-dimensional form primarily in the design of its cars, which has been described as avant-garde, rational or progressive, and which combines function with elegance (Rosengar- ten & Stürmer 2005). Audi transferred these brand attributes to the architectural concepts for its centers. The car salesrooms built before 2007 feature a technical, reserved style with an open glass and steel architecture. The main recognizable feature of these buildings – in ad- dition to the Audi logo and lettering – is the curved roof.

Audi commissioned the architects firm Allmann Sattler Wappner to re-interpret the concept of car dealerships. The result is the “terminals”, which are designed to better reflect modern demands in terms of mobility and the altered needs of the consumers. In June 2008, the automobile manufacturing group opened the first of its new terminals in Munich. The new local salesrooms, which are being built across the world (by the end of 2012, more than 350 Audi Terminals are to be built worldwide, Audi 2008), are intended to create more than just a transit space: the architectural concept takes a holistic approach and presents a three-dimen- sional experience that goes beyond functional requirements with regard to the presentation, customer service and the sale of the products. The Terminals are designed to make the cus- tomer’s visit more enjoyable and to convey Audi’s brand world; the distinctive aesthetic of the building should be identifiable at every lo- cation, worldwide.

Architecture as a presentation platform

For long-term successful communication it is essential that the target groups remember the brand communication and associate posi- tive feelings with it. The technique of ‘storytel- ling’ is playing an increasingly important role in this context (Herbst 2008). By telling stories, companies can trigger emotions among the target group, to help anchor the brand in their memory over a long period of time. Storytel- ling can also be used in the communication of architecture, e.g. temporarily, as is the case at trade fairs and events, or continually, as in salesrooms and fixed worlds of experience.

Temporary brand staging

Trade fairs, such as the biannual International Motor Show IAA in Frankfurt, garner inter-

national media attention and represent an important communication platform for car manufacturers, particularly when introducing new models. The shows predominantly target industry specialists and media representatives, but, increasingly, interested members of the public are also visiting presentation platforms of this kind. With their trade fair presence manufacturers hope not only to disseminate product information and present their models in the best possible light, but also to convey the existing values of the product brand and the company. Through the combination of space and design, architecture provides a plat- form for brand staging. The brand values can be communicated as a first-hand experience and imbued with emotion.

In the context of a temporary brand staging, architecture must fulfil three functions: the un- usual and impressive staging should increase the likelihood of media coverage; it should convey the strategic core message in a striking and clear manner; and finally, the architecture should optimally convey the brand values and anchor it effectively in the minds of the target group.

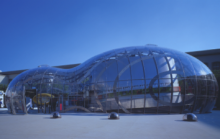

As explained above, stories can effectively convey and anchor brand messages. One com- pany that aims to create stories through archi- tecture, telling them through spatial means, is Franken Architekten. A successful example of the realisation of visual storytelling is the BMW Group’s trade fair presence at the IAA in 1999. The objective was to architecturally convey the strategic focus of the car manufacturer with regards to environmentally friendly and energy- efficient driving. Franken Architekten translat- ed BMW’s communicative message and brand values in an exhibition building in the form of Bubbles. The iconic form of a computer-simu- lated drop of water conveys the idea of driving with “clean energy”. The organic shape gives the building a natural look-and-feel, which is underlined by the design metaphor of the wa- ter droplet (Franken Architekten 2009). The glass shell conveys an open and transparent character. The mix of glass and steel adds a fu- turistic touch and emphasises the visionary ap- proach to the issue and the technological and innovative claims of the company.

Permanent places for brand staging Another form of long-term brand staging in the automobile industry are the museums created in the last few years by Mercedes-Benz (opened 2006) and Porsche Museum (opened 2009). A highly regarded example of permanent brand staging is the Volkswagen Autostadt.

The Volkswagen Group underwent a compre- hensive process of change under Ferdinand Piëchs: on the one hand, it was important to the company that it no longer be perceived only as a car manufacturer, but also as a mo- bility service provider; on the other hand, the group significantly broadened its range of products in various segments and bought up a number of well-known brands. The range of products produced by Volkswagen Group ranges from the more down-to-earth brands like Skoda and Seat, Audi and Volkswagen through to the elegant Bentleys and Bugattis and the racy Lamborghinis. The result was that

the public no longer had a clear image of what the brand stood for. The Volkswagen Group’s goal in the Autostadt is to enable its customers to experience the brand values through spatial presentation; these values include quality, per- formance, sustainability and customer proxi- mity. The architecture firm managed by Gunter Henn created a space spanning 25 hectares, where pavilions, waterways and bridges, lakes and promontories, hills and lawns, give the im- pression of a self-contained town with a cen- tral focus on the automobile and mobility (Au- tostadt 2009, Henn 2009).

Brand communication occurs on various levels within the Autostadt: one of the central fea- tures is that the customer can collect his new Volkswagen direct from its ‘place of birth’. The vehicles stand ready for collection by their new owners in one of two 48 metre high towers, which can be seen from afar and have become a landmark of the Autostadt. The handover it- self takes place on a representative stage and is transformed into an unforgettable experi- ence for the customer, and the intention is that it will be a day of many fond memories. In ad- dition to exhibitions and events on all aspects related to cars and mobility, visitors are intro- duced to and familiarised with every brand be- longing to the Volkswagen Group in a separate dedicated pavilion.

Architecture as a locational feature BMW succeeded at a very early stage in con- structing a formative feature of urban archi- tecture. The car manufacturer made architec- tural history and has built various landmarks

at its central location in Munich over the last few decades: the company headquarters, the museum and BMW Welt. First came the tower, known as the ‘four cylinder’, which houses the company headquarters. The building was com- pleted in time for the Olympic Games in 1972 according to the plans of Austrian architect Karl Schwanzer. It symbolises one of the core elements of a car manufacturer – the cylinders of the motor. Schwanzer built the adjacent BMW Museum at the same time as the com- pany headquarters. The special feature of the round, futuristic looking building is the huge BMW logo on the flat roof, which journalists refer to as the ‘museum cup’ while the locals call it the ‘salad bowl’ or the ‘Weißwurst caul- dron’. Of the German car manufacturers, BMW is seen as the engineer’s brand, whose tech- nological and development skills are clearly ex- pressed in the innovative design of the build- ing. Despite the fact that all BMW logos had to be removed from the buildings for the du- ration of the Olympic Games, the avant-garde, unique appearance of its buildings generated a high degree of press interest for the company and, thus, a high profile internationally.

The BMW Welt was built as a complementary structure in 2007. This building, constructed by the team of architects from Coop Himmelb(l) au, was designed to create an integrated BMW experience. The central feature is the staging of vehicle collection: the handover to their new owners of around 45,000 cars annually

is transformed into a highly emotional and sensory experience through the symbiosis of architecture and service, which binds the cus- tomer to the BMW brand long-term. In addi- tion to the way the handover is staged, the building has to fulfil three additional functions: product presentation of BMW models; presen- tation of technological and development skills; and providing a space for all kinds of internal and external events. The objective of the BMW Welt is to translate the brand message “Freude am Fahren” into a three-dimensional brand experience, which can be experienced with all the senses and conveys the identity and allure of the brand (Shell 2004). This direct, emotion- al address to the target group is intended to make the abstract brand BMW into something tangible; an experience - a strategy that paid off for this car manufacturer.

The three BMW buildings have become a fixed and characteristic part of Munich’s cityscape. The newly built BMW Welt in particular is a major attraction for locals and tourists alike. Since its opening on October 17, 2007, more than 3 million visitors have come to see this brand world. This makes the brand world the second most popular landmark in Munich (BMW 2009).

An example of an instance in which the trans- fer of brand values to architecture and the shaping of a cityscape was not successful is the Mercedes-Welt in Berlin, which opened in 2000. Despite a top central location it was not possible to convey emotional brand values and create features that generate attention.

Problem: Architect’s Brand vs. Company Brand

Many of the new automobile buildings were created by renowned architects or firms, such as Zaha Hadid or Coop-Himmelb(l)au. Here, one must question whether the final result actually reflects the brand values of the ar- chitect, rather than those of the company for which they were designed: it is apparent that architects have a strong, individual visual style, which is evident in designs for different clients. Zara Hadid’s use of form was very similar in both the BMW centre in Leipzig and the Sci- ence Centre in Wolfsburg, which is located op- posite the Volkswagen Autostadt.

The highly regarded BMW Welt, designed by Coop Himmelb(l)au also bears the architec- tural signature of that firm – the double cone and the floating cloud roof. The strong individ- ual style of architects and firms can have both advantages and disadvantages for the compa- nies employing their services. Images can be transferred in two directions: first, the positive image of a star like George Clooney can have a positive effect on a brand like Nescafé; second, the product image can transfer to the owner of the product, as the example of the Apple iPhone illustrates (Rosenzweig 2008). Applied to corporate architecture, this means that the image of a star-architect also affects the com- pany building and can entail an additional im- age transfer as well as generating publicity. Many press representatives deem the mere commissioning of a renowned architect such as Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid or Norman Foster worthy of a press release. This can, however, become problematic where an architect that uses such a unique individual style works for various large companies with strong brands, meaning that it is no longer possible to clearly allocate or to associate the building with the brand.